The enthralling tale of the lizard within

Introduction

It is very difficult to evolve by altering the deep fabric of life; any change there is likely to be lethal. But fundamental change can be accomplished by the addition of new systems on top of old ones.

Carl Sagan - The Dragons of Eden.

Carl Sagan (1934 - 1996) was an American astronomer, cosmologist and a science communicator. He played a leading role in the American space program as he was a consultant and adviser to NASA. He carried out significant research in planetary science and created a television series called Cosmos in which he focuses on the origin of the universe by discussing the Big Bang, Galaxies, and the expansion of the universe. He was the author of many best-selling popular science books, one of which the opening quote of this post was taken from; The Dragons of Eden $-$ a book that won him a Pulitzer Prize in 1977.

The Dragons of Eden offers to explain the evolution of the human species from the beginning of the Big Bang to our current time period. Sagan looks at clues from a wide variety of sciences including anthropology, biology and psychology to support his reasoning. He devotes a large part of the book to the human brain, focusing on how it functions and how it differs from other animals. Sagan draws on a model of the human brain evolution, called the Triune Brain, to account for the Sonderstellung of humans among the realm of living beings and how we evolved to produce art, music, math, science and other aspects of our mind that make us “unique”.

The idea of the Triune Brain goes back to the 1960s, where an American neuroscientist Paul MacLean described the brain as a hierarchical organization, gradually acquiring its different structures through evolution, like a geographical strata.

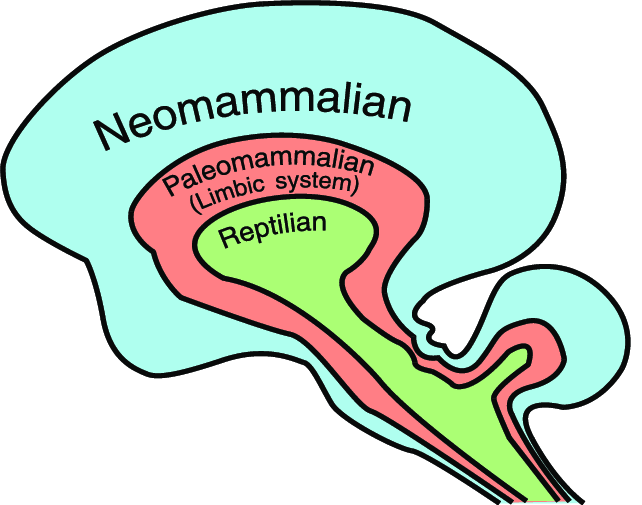

Figure 1: The brain structure as proposed by Paul MacLean. (Source)

According to MacLearn, the human brain “amounts to three interconnected biological computers”, each with “its own intelligence, its own subjectivity, its own sense of time and space and its own memory”. MacLean went on to hypothesize that each one of these separate brains corresponds to a major evolutionary step. Worded differently, MacLean was suggesting that every human brain contains three independent subjective consciousnesses.

Figure 1 shows the hierarchical structure of the human brain as described by the Triune Brain model. The deepest layer, the bottom most and most ancient is termed the Reptilian brain or the lizard brain. It is called so because, according to this model, we share it with any ancient creature. The Reptilian Brain or the R-complex as MacLean likes to call it, was wired for basic urges like feeding, fighting and mating and is the house for survival instincts. Sitting on top of it is the limbic system, inherited from prehistoric mammals. It is supposedly responsible for emotions — fear, anxiety, arousal, all those belong in the limbic system. The outermost layer - the neocortex is said to be uniquely human and its the source for rational thoughts. MacLearn refers to it as “the mother of invention and father of abstract thought”. Its main job is, supposedly, to regulate the emotional and lizard brains to keep irrational thoughts and animalistic behaviors at bay.

As it turns out, a thorough inspection of MacLean’s theory shows that it doesn’t hold up. In what follows, I will be exploring some arguments from different disciplines, including Darwinian evolution, genetics and embryology, that undermines MacLean’s model. A great deal of these arguments are taken from a delightful, slim but potent book called seven and a half lessons about the brain by neuroscientist Lisa Feldman Barrett. I have found this book an interesting read as it poses some interesting questions, such as “Why did brains evolve?” and “How our brains predict almost everything we do ?”, while busting many of the scientific myths about the human brain. One myth that has particularly caught my attention is the Triune Brain; the subject I will be addressing in this post. I decided to write about it to better understand its origins and further explore the arguments undermining it. Finally, I will be looking at potential reasons why this faulty theory has made its way into the cultural mainstream.

The Triune Brain: an abandoned theory

Darwinian evolution standpoint

In a recent paper called Your Brain Is Not an Onion With a Tiny Reptile Inside, published in 2020, the authors raise a point regarding this prevalent misconception in psychology that vertebrate animals have acquired newer complex brain structures on top of old ones through evolution, allowing them to acquire new and more complex psychological functions. This misconception the authors are debunking have its origins in the Triune Brain model of MacLean, which is apparently still a belief, widely shared by some psychologists and in most introductory textbooks, even if it has long been discredited among neurobiologists. By the way, if you have ever listened to some “self-help” or “motivational” speeches, you almost certainly have come across this wrong view of the brain. However, the authors of this paper described the more accurate model of neural evolution from a Darwinian standpoint.

Figure 2: The incorrect view of Darwinian evolution. (Source)

Given that primitive species are lacking outer and more recent brain structures, according to the Triune Brain model, the evolution of the different parts of the human brain happened linearly, as shown in (b). Thus, this model stipulates that the evolution of the different animals happened linearly as well (a), increasing gradually in complexity, which is an incorrect view of Darwinian evolution.

Figure 3: The correct view of Darwinian evolution. (Source)

The correct view of Darwinian evolution is shown in the evolutionary tree (c). It illustrates that indeed animals do evolve, but not in a linear increase of complexity. They evolve from a common ancestor. The coloring in the corresponding view of brain evolution (d) also illustrates that all vertebrates possess the same basic brain regions. These brain regions do differ in form and size from one species to another, but no new layers are being added on top of others over the course of evolution.

The key point to take away is that just as species did not evolve linearly, neither did their neural structures. Therefore, rather than thinking of evolution of brains as some chain leading up to humans as a pinnacle, it is much more accurate to think of it as a tree exploring different structures, and keeping the ones that fit better in their proper environment.

Genetics standpoint

Figure 4: Comparison between a human and a rat brain. (Adapted from Source)

Back when Earth was ruled by creatures without brains, these creatures’ simple bodies were managed by a handful of cells to act in and react to their environment. As creatures evolved more complex bodies, body-budgeting became a challenging task, especially as the Earth entered the Cambrian era where hunting starts being a thing. Creatures needed something more than a handful of budgeting cells to manage their bodies. How can I avoid danger ? How am I going to know if it is time to grab a piece of food ? How am I going to remember that the last time I was in this particular place, it does not ended up well ? Creatures expressed the need to answer this kind of questions. They needed a brain whose job is to ensure that resources were all regulated well to keep the body running efficiently and to prepare the body to react to any danger that may be threatening it. Therefore, as the body has evolved, the budgeting cells also evolved to become brains of greater complexity. The size, shape or neural densities may vary across species depending on the cranial capacity and the body that has to be managed. We can’t fit a human brain into a rat cranium, and putting a rat brain into a human cranium is such a waste of space. One may then wonder where the difference between a rat brain and a human brain comes from? In any case, to the naked eye, the difference is obvious, isn’t it ? Even more so if we compare what we as humans are capable of, compared to rats. Rats did not put their feet on the Moon nor build skyscrapers.

It turns out that comparing brain structures using naked-eye examinations is misleading, even if it can sometimes be tempting, especially at a time when technology was less sophisticated and did not allow this examination to be done in any other way. For example, as it is shown above in Figure 3 - (d) and Figure 4, one can easily conclude that the human brain seems more complex than the rat’s. A bigger brain with a bigger neocortex (the top part of the brain), with much more folds, and all this backed with our behavioral capacities compared to rats. But it transpires that neural cells (or neurons), which are the building blocks of any brain out there in nature, can look very different to the naked eye but still contain the same genes, implying that those neurons have the same evolutionary origin. Using the same example as before, if we were to find the same genes in human and rat neurons, this means that these genes most likely were present in our last common ancestor, and we both have inherited them. In her book, seven and a half lessons about the brain, neuroscientist Lisa Feldman Barrett gave a very interesting example regarding this subject. There is a brain region called the primary somatosensory cortex. It senses tactile information — creating the sense of touch — and the body movement. In the human brain, this region is divided into 4 areas. Whereas, in a rat brain, this same region contains only one area. Inspecting the human and rat brain by eye lead us to conclude that 3 regions of the primary somatosensory cortex have newly evolved in humans, therefore being responsible for human-specific functions. The reality is that these regions in the human and rat brain contains many of the same genes. This implies that the same inherited region has expanded and subdivided to redistribute its responsibilities as our ancestors grow larger in both bodies and brains.

Another point I believe that is worth noting has to do with rationality being a product of the size of the human brain and its regions compared with other animals, in particular the cerebral cortex. It is common belief that the cerebral cortex has grown larger through the course of evolution, leading to a species called Homo Sapiens that believes it is carrying the seat of intelligence and rationality under its skull. This view is wrong. In fact, the size of the cerebral cortex is not evolutionary new and it does not say anything about how rational a species is. Rationality, as Lisa Feldman Barrett has defined it, means making a good body-budgeting investment in a given situation by spending or saving resources to succeed in your immediate environment. Finally, if we were to include relativity every time we compare brain regions, the human cerebral cortex is not large given the overall brain size. In fact, it is a scaled-up version of the relatively smaller cortex of a chimp and is a scaled-down version of the larger cortex found in the larger brains of elephants and whales.

Bottom-line is that the human brain is not more evolved that a rat brain. It is just differently evolved. Each brain has taken a different evolutionary path, shaped by the environment it has found itself in.

Embryology standpoint

Another great discovery that undermines the evolutionary foundations of the Triune Brain has to do with embryology. Embryos, of both humans and animals, go through similar stages of early development. The main difference lays in how long it takes to reach each of these same stages. This does not exclude the development of the nervous system. In fact, mammals, reptiles and other non vertebrates have their brains following similar conception stages. These conception stages last for shorter or longer durations depending on the species at hand.

An example that neuroscientist Lisa Feldman Barrett cited in her book seven and a half lessons about the brain concerns the difference between the manufacturing process governing the conception of the human cerebral cortex compared with rodents and lizards. The process producing neurons for the cerebral cortex in humans runs for shorter time in rodents and a much shorter time in lizards. Consequently, the human cerebral cortex is large, the rat’s is smaller and for some reptiles is tiny or nonexistent. “In theory, if we find a way to reach into a lizard embryo and force that stage to take as long as it takes in humans, it would produce something similar to a human cerebral cortex.”

The take-away from this discovery, another time, is that we are not the point in the animal kingdom. Our brains aren’t the most evolved out there in nature. In fact, they do not differ from rodents’ or reptiles’ — creatures that are supposedly less evolved than humans, according to the Triune Brain. It turns out that our brains are governed by the same processes and are made up of the same building blocks, even those that compose the neocortex, which is believed to be the seat of rationality and abstract thinking — a gift supposedly Mother Nature has given to humans only.

How the Triune Brain made its way into the cultural zeitgeist ?

In my opinion, one of the reasons why the Triune Brain model has so captured people’s imaginations and gained in notoriety is that it is intuitive, elegant and consistent with old, widespread and well-believed hypothetical structures of the mind. In fact, it is a neuroanatomical mapping of these old conceptions about the human mind onto the brain.

More than 2000 years ago, Plato suggested in his famous dialogue Phaedrus, the three basic elements of human nature: will, emotion, and rationality. Plato goes on to compare the human soul to a chariot being pulled by two horses moving in opposite directions and a charioteer trying to control it. In the lens of the Triune Brain model, the neocortex would be the charioteer wrangling with the two horses: one is the R-complex, and the other is the limbic system.

The Triune Brain model also parallels Sigmund Freud’s conception of the human psyche. Following this tripartite model of psychoanalysis warring the superego, ego and id, one can easily draw parallels between MacLean’s physical conception and the functional conception of the human brain as was imagined by Freud.

Another reason I believe that has contributed to the wide spread of the Triune Brain model is the The Dragons of Eden. As discussed in the introduction, the Triune Brain theory played a starring role in Carl Sagan’s bestseller and Pulitzer Prize winner. Consequently, partially by way of Sagan’s eloquence and enthusiasm, coupled with the huge audience he had, MacLean’s faulty theory has found its way into the cultural mainstream.

Conclusion

To believe in the triune brain is to award ourselves a first prize trophy of Best Species.

Lisa Feldman Barrett - Seven and a half lessons about the brain.

Paul MacLean introduced the concept of the Triune Brain in the 1960s. This model of the human brain is based on three specific regions $-$ the reptilian brain, the limbic system, and the neocortex — one on top of the other, each is believed was acquired through the course of evolution. MacLean suggests that each of these structures is responsible for a specific group of mental activities. The reptilian brain is responsible for the fight-or-flight survival response and other primal activities, the limbic system for emotions, and the neocortex for rational thinking and controlling the lower inner beasts.

However, while the Triune Brain model provides us with a sleek way of looking at the relationship between structure and function in the human brain, evidence from various scientific disciplines has shown that this theory does not hold up under scrutiny. Therefore, there is no such neat division. Instead, primal, emotional and rational mental activities are the product of neural activity in the whole brain, functioning as a network, with more than one of the three regions addressed in MacLean’s model. This collective neural activity is what creates the human experience.

References and further reading

Rethinking the reptilian brain

A theory abandoned but still compelling

Extended notes for the book Seven and a Half Lessons About the Brain

Your Brain is Not an Onion with a Tiny Reptile Inside

3D Brain anatomy: a cool tool to explore interactively the different brain structures